Like many who visited the October 2023 NEC show, I found the prices of new models eye-watering. There was the usual array of glittering ’vans and some brilliantly inventive packaging and novel layouts. But the overriding theme was the pricing. It got me thinking, what could I do to prolong the life of my motorhome?

In 2016 I bought a top-spec Renault Trafic van for £17,000 from a Renault main dealer, then spent some £20,000 having experts convert it. So it owes me around £37,000 in total.

Today, that wouldn’t even buy you the base vehicle, and a fully converted Renault Trafic to a similar specification would cost around £70,000 or more.

The best camper vans all seem to start at £50,000 to £60,000, while a top-spec VW Transporter and other luxury campervans will be north of £100,000.

If you’re thinking of trading in your old motorhome – as many people do after three or four years – that’s quite a chunk of cash to find, or a lot of finance to arrange to bridge the gap. And with interest rates relatively high these days, neither option is cheap.

You can point the finger at Brexit, wars, silicon chip shortages, the economy and the energy crisis, but that doesn’t change the facts – buying a motorhome isn’t cheap.

Like many owners, I’ve now decided to stick with what I have and run it for a few more years. But what do you need to know to keep your ’van reliable and healthy in the longer term? In short, how do you prolong the life of a motorhome? In this guide, I’m talking you through the different motorhome maintenance tasks you can have done.

Sleepy ’van syndrome

Probably one of the biggest issues that affects ‘vans is lack of use, something that can become an issue when winterising a motorhome. This might sound odd, but having a vehicle stationary for long periods over winter never does it much good.

The key problems are with rubber items, such as drivebelts and cambelts in the engine, together with tyres that are left standing in one position.

It’s a similar story with water ingress: having a vehicle parked in one spot can increase the chances of water pockets gathering on the roof and creeping into any seams. Standing water is excellent at exploiting cracks and crevices and inconveniently expands when frozen.

Driving the vehicle regularly avoids belts lying dormant in one position and helps to rotate the motorhome tyres, avoiding flat spots. Equally, it can help shake off trapped water on the roof and prevent this freezing and causing damage. Take a look at what you can do for your motorhome tyre pressure too.

So the ideal thing to do is to use the vehicle over the winter, or at least take it for a drive of more than 20 miles or so every couple of weeks.

A dash around the block won’t get the engine up to operating temperature and is not recommended for diesel engines, as it greatly increases the risk of engine wear and build-up of carbon in the emissions control systems.

Modern diesels hate short journeys and rely on the occasional burst of high revs and motorway speeds to help them get hot enough to burn off the carbon deposits that can build up on excessive short journeys. Low revs and brief runs are the surefire way to bring on diesel particulate filter issues and MoT emission failures owing to carbon build-up (see: how to help your motorhome pass its MoT).

If you’re storing your motorhome remotely and are unable to use it regularly over the winter, you need to have it serviced religiously; pay extra attention to the engine belts’ service interval times.

Engine servicing

Most leisure vehicles are based on a van or a truck. These are all designed to be used in a commercial environment and are typically engineered to run for as long as possible between services.

Often, the engine oil change can be as much as 20,000 miles. On a typical white van that covers 100,000 miles in three years and then gets renewed, this isn’t a problem and every few months, it will be back at a dealership being serviced and safety checked.

Leisure vehicles rarely do such high mileages and the danger is that they can go for long periods without being checked or serviced by a dealer. This might be enough to satisfy the terms and conditions of the warranty, but it isn’t wise for long-term safety and reliability. Especially in the case of vehicles that cover annual mileages of less than 5000 miles.

You’ll also typically find that large van- or truck-based motorhomes (that is, Fiat Ducato base vehicle sizes and larger) tend to be second vehicles and cover lower mileages than VW Transporter sized campervans.

It’s easy to think that gentle motorhome use and low mileages will make these hardy commercial vehicles last forever. But this isn’t the case.

In reality, a motorhome is a van that is nearly always driven fully laden (all that furniture and bodywork means most will run near to their maximum payload most of the time). So tyres take a pounding, engines have to work hard (especially from cold on short runs) and the suspension is always working hard. Which all means it is prudent to have your vehicle serviced annually, no matter how many miles it covers.

For your motorhome, you also have to consider how many cold starts they do – these are the events that cause the most engine wear.

What happens when you turn the key on a cold engine is that, for a brief period, the piston rings are reliant on the oil film clinging to the bores of the cylinders, and there is always a small amount of fuel that bypasses the piston rings and oil control rings in start-up. Piston rings have a tiny gap that closes to form a tight seal as they expand with heat. From cold, the gap is there and it is the first few minutes of start-up that can cause tiny amounts of wear. The more cold starts, the more wear.

Modern multigrade oil is designed to deal with this and is thinner when it’s cold, so the oil pump can rapidly pump the oil to the bearing surfaces and allow the crank (or oil control sprays) to throw oil onto the cylinder walls to prevent wear.

At first start-up, the only oil on the cylinder walls is the oil still clinging on from a previous start. Cylinders often have various coatings on them to reduce friction and wear, but they still work better with an oil film.

Once the engine is up to temperature, the oil thickens to allow for expansion of the various metal parts in the engine and forms a wear barrier between such surfaces as the crank bearings and big end bearings in the conrods.

Oil degrades with the number of cold starts and time, as well as the mileage. Contaminants from cold starts – such as carbon and diesel – build up in time and although all oils contain detergent and friction-modifying additives, there is a limit to what they can do.

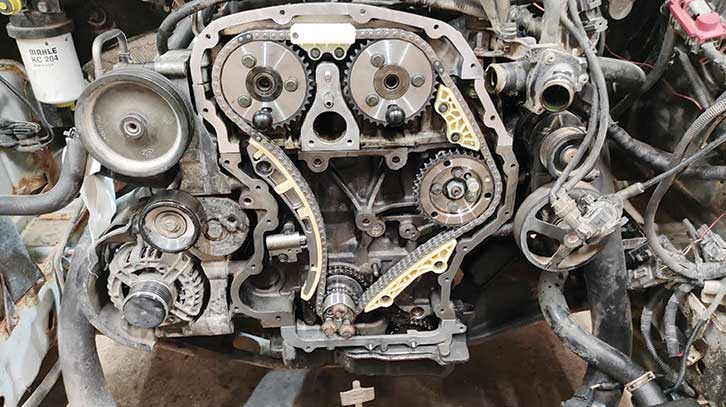

Some modern engines also have a timing belt that runs in the engine oil, which can cause rubber debris (and even the teeth) to contaminate the oil. These particles and debris degrade the oil and reduce its efficacy. Oil is the lifeblood of an engine and the most vital part of its longevity.

Only use the grade of oil (for example, 5W-30, which relates to viscosity cold and hot) given in your manufacturer’s handbook. Don’t rely on internet forum recommendations, which are too often wildly inaccurate – they often relate to countries with very different climates, which have zero relevance to the UK.

As well as the correct grade, make sure the oil is the right specification for your engine. Europe uses the ACEA (European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association) specifications for rating oil, from A1/B1 to A5/B5.

A is for petrol engines, B for diesel. The numbers relate to a precise spec to suit your engine. For example, A3/B4 is for direct-injection diesel engines, while Low SAPS (sulphated ash, phosphorus and sulphur) oils contain additives to reduce ash in the diesel. This ACEA specification is very important and just lobbing in any old 5W-30 oil is a surefire way of getting problems in the long run.

It’s also important to check your engine oil regularly and keep it topped up to the maximum at all times. This is not only good practice, it also acts as an early warning of future issues. If you suddenly find the engine is using more oil than normal, you can investigate before this becomes a bigger problem.

Timing belt or chain?

Your ’van’s engine is best thought of as an orchestra of moving parts. As the pistons move up, the valves must open at a precise moment to let in fresh fuel/air or expel spent gases.

The timing of these events has to be ultra-precise, which is why the latest engines use variable valve and cam timing, together with all manner of clever fuel-injection systems and all controlled by the ECU (which is like the orchestra’s conductor).

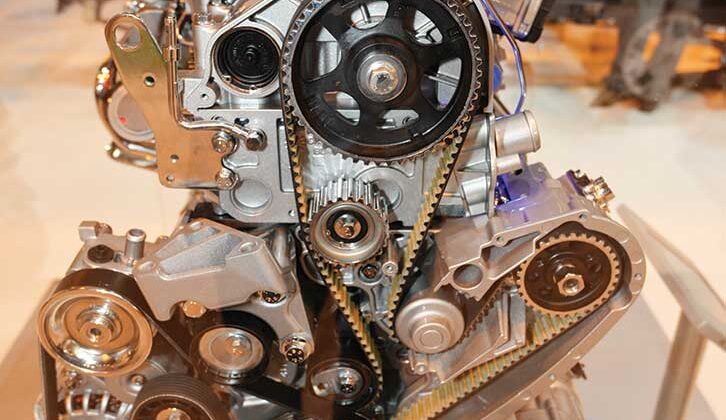

But it’s not all about the electronics – the crank is always connected to the valvetrain by mechanical means. This will be by means of metal gears, a rubber-toothed timing belt (or cambelt), or a metal timing chain.

To maximise their efficiency, most modern engines are ‘interference engines’, which means the valves can occupy the same space as the piston, but crucially, at different times.

If, for any reason, the valves and pistons get out of sync – a cambelt snaps, for example – they can collide and this is nearly always catastrophic for the engine. At best, you’ll have lots of bent valves and need a new cylinder head; at worst, the valve heads can snap off and punch holes through the pistons, often destroying turbos and catalytic convertors as debris exits the engine via the exhaust. In short, it’s new engine time.

It is generally thought that gears or timing chains are the most durable of components and it’s a big plus if your engine is equipped with this system. But they still have a service interval, which must be adhered to.

Modern ones are also durable, but cambelt replacement will be necessary at set mileages or – much more relevant to motorhomes – at set timings.

This is often at five-year intervals (for example, for Fiat Ducatos), and they usually come as a complete kit that also includes the belt tensioners and water pump. Always check for proof of a cambelt swap on a used ’van and never go over the yearly time for swapping (even if you’ve only covered a few thousand miles).

If you have an engine that has a ‘wet’ cambelt (also known as timing belt in oil or TBIO) which runs in engine oil, the cambelt swap time is even more critical and the oil change interval is extra important.

There have been cases of cambelts past their change interval shedding rubber dust, even teeth. Debris can gum up the oil pump filter head, causing reduced oil pressure and lowering the lifespan, while missing teeth hugely increases the chance of engine failure.

Where to buy fuel

This is a much easier one – anywhere! Most forecourt fuel, whether it be from a petrol station, a supermarket, a local supplier or motorway services, comes from a similar source and is controlled by British Standard regulations.

The idea that supermarket fuel is in some way inferior is nonsense, as most retailers share the same refineries.

The only factors that can affect fuel quality are the age of the underground fuel tanks and the detergent packages added by the retailer you’re using.

Typically, regular petrol or diesel will have minimal additives, while higher-octane diesel/petrol will have a higher level of detergent and fuel cleaning additives (and lower levels of ethanol biofuel). It’s wise to refill the tank with posh fuel after a long lay-up and every few fill-ups, but not essential. Use an app to find the cheapest fuel.

Another point is to avoid filling up just after a fuel delivery tanker has replenished the petrol station tanks. This is because it disturbs all the gunk and debris that is always found at the bottom of bulk storage tanks.

Most retailers won’t allow you to fill up after a tank fill and leave a certain period of time after a delivery, but this can vary. Equally, rural forecourts can often have ancient fuel tanks that may contain more debris.

The fuel is filtered and water content (from condensation) is monitored on all forecourts, and your vehicle’s fuel system has at least two further filters, but if you have a choice of two petrol stations, always pick the newest. This highlights the importance of regular maintenance in replacing the filters.

One thing I’d avoid (often detailed on the fuel cap in modern vehicles) is any form of fuel additive. Catalyst cleaners, fuel octane boosters and detergent additives, all sold at petrol stations and motor factors, should be treated with great care – they can invalidate your engine warranty.

Which? magazine once did a useful test of in-tank additives and was unimpressed with many of them. Most did nothing, some caused harm. I’d suggest saving your money – all the detergents and additives your engine needs are in the fuel.

Much has been written about the latest biofuels, with E10 petrol (which is up to 10% plant-based ethanol) getting a lot of criticism. Diesel has been biodiesel (up to 7% ethanol) for some time, without as much online chatter. In Europe, you can buy fuel up to E85 (85% ethanol). There is no issue with under 10% concentrations used in the UK, but it is worth noting that this is on modern vehicles which have been designed to run on biofuel.

If you have a pre-2000 vehicle, the Government website lets you check if it can run on E10.

Generally speaking, if your vehicle has plastic fuel lines, it’s designed for biofuel. Where issues have arisen with biofuel, it has been when a vehicle is left for a time with a low fuel level, and internal rubber components – often on fuel lines or older carburettors – have dried and cracked. Biofuel is chemically aggressive and can eat into these older materials. However, modern ’vans use materials such as Viton, which is much more resistant to biofuels.

Most criticism of ‘biofuel issues’ can be traced to poor vehicle maintenance and failure to renew rubber parts at the correct interval. As always, servicing and maintenance are the key.

Once you’ve sorted this out, it will be time to think about your motorhome fuel consumption.

Warranties

Most base vehicles have a three-year warranty, which usually lasts for up to 100,000 miles (Volkswagen, for example). It varies from manufacturer to manufacturer, but this is typical.

Many also offer the option to extend the warranty by a few years. This is worth doing, so check the terms and conditions with the motorhome manufacturer.

Many vehicle suppliers will also offer a bodywork warranty, which is usually called an ‘antiperforation’ warranty and can last years (12 years for Crafter and Transporter, for example), as well as a paintwork warranty.

To maintain these warranties, you are usually required to have an annual inspection stamped in the service book (or in the digital service history) and this often carries a charge.

Sometimes, the annual inspection cost is quite high and this does make it debatable whether it’s worth doing. It might work out cheaper simply to pay the money to a bodyshop for any future work that’s needed.

Bodywork and paintwork warranties won’t cover you for stone chip damage, and only encompass defects that occur inside the metalwork and then bubble to the exterior. This can be a problem, as it’s very difficult to prove how a bodywork hole started over time.

It’s well worth investing in a pot of touch-up paint and getting into the habit of touching in small defects on a regular basis. Check the leading edge of the bonnet and the wheel arch edges (especially underneath, where stones are often flicked up) and touch in chips when you spot them. Most wheel arch corrosion starts with a stonechip.

Don’t use the brush supplied with the paint pot (it’s usually far too big) and instead, buy a selection of cheap paintbrushes. These cost a few quid online or from craft shops and allow you to make much neater repairs.

You can also buy a product known as Paint Protection Film for the leading edge of bonnets and wheelarch edges. This self-adhesive film is surprisingly effective and the modern versions absorb stone chips and can self-heal to a certain extent. However, they are not particularly cheap.

In my opinion, one product to avoid is a bonnet protection bib (also known as a bonnet bra or bonnet protector). These are usually some form of vinyl lined with soft fabric on the side that goes against the bonnet.

They’re held on the vehicle with straps and clips (which can chip the bonnet edge). The problem is that over time, dirt and debris are potentially washed down and trapped between the bib and the bonnet. As the bib moves in the airflow (which can be well over 70mph if there is a headwind on a motorway), this dirt can start to sand through your paintwork, causing unwelcome damage.

Habitation kit servicing

Of course, it’s all well and good having a beautifully maintained vehicle that can reliably take you to a campsite, but if you don’t look after your habitation equipment equally well, then it can let you down. It’s highly recommended to have an annual habitation service at an NCC-approved workshop.

The most important safety aspect of this servicing work is the gas check, which makes sure the burners in the hob, fridge and motorhome heating system are all burning efficiently.

Any indication of yellowish flames, flickering, or irregular flame fronts on the hob is bad news and means it could be producing excess carbon monoxide. This is highly dangerous – do not use any hob that is not burning even blue flames until it has been checked.

Habitation inspections also protect your investment, by looking for water leaks in the plumbing system and water ingress from body seams and seals. Dealers use high-end detectors to look for evidence of damp and can often spot the start of such problems before it becomes a far larger issue.

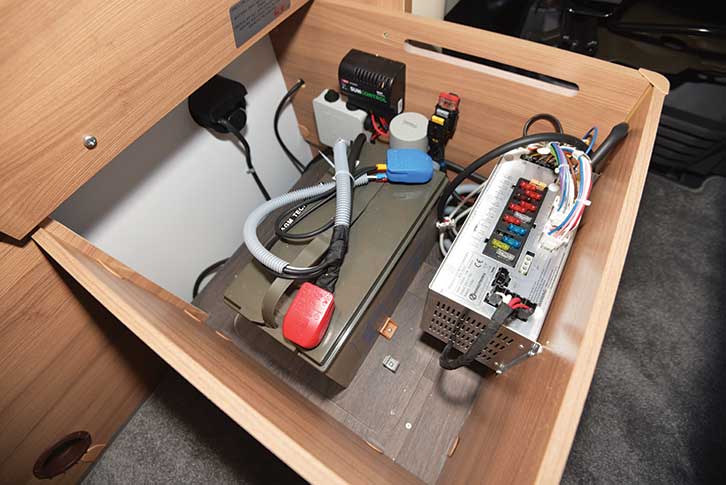

Batteries tend to be the number one problem for motorhomes and as the entire habitation area relies heavily on them, they should be checked at the start of every season. Always keep the campervan leisure battery topped up by plugging the ’van into the mains in winter, or using a battery conditioner.

Every time you allow your leisure battery to go flat, you damage it a little bit and reduce its lifespan.

It’s also well worth thinking about upgrading to a LiFePo4 unit – these are far more tolerant of varying voltages. If you’re considering a lithium battery, check out the pros and cons too.

Sourcing parts

One difficulty that is cropping up more and more on all models of base vehicles is sourcing of spare parts.

Do not buy the lowest-priced parts you can find on eBay or Amazon – many are cheap items from overseas and of poor quality. This is particularly true of electrical and engine parts. While online prices can look temptingly cheap, the quality can be pretty dire.

It helps to be aware of the reputable brand names for electrical items – stick to established brands such as Bosch, Denso, Magnetti Marelli and Valeo, for example. For things that bolt to your engine or drivetrain, it’s best to keep to a branded item of OE quality.

This problem was highlighted very recently with an alternator failure on my son’s car. The cheap, imported alternator was around £100 cheaper than an OE Bosch one, but after taking the failed unit to an alternator rebuild specialist, we discovered that it had partially disintegrated inside and the plastic coil covering material had melted and gummed up the interior.

Fortunately, the alternator in my son’s car had stopped charging, but these units have also been known to catch fire. A potential hazard and very much a false economy.

Pattern parts made to OE quality are fine, but be very selective about where you source parts from and if there is a choice of two brands, always pick the one you’ve heard of. Poor-quality pattern parts are rarely worthwhile and will never outlast OE parts.

The verdict on prolonging the lifespan of a motorhome

The vast majority of problems with modern motorhome longevity will often stem from poor or infrequent servicing and the use of low-cost, low-quality parts.

Oil and filter changes won’t break the bank, but will keep the vehicle in tip-top condition and are especially important on low-mileage ’vans that experience greater carbon build-up. Habitation servicing is as important as looking after your base vehicle – a vital health check for onboard systems. Taking the time to carry out these checks could make a big difference in allowing you to prolong the life of your motorhome and save you needing to splash out on a new one.

While you’ll hopefully never need to use it, it’s crucial to have the best fire extinguisher for a camper van to hand too. It can provide you with some valuable peace of mind.

Future Publishing Limited, the publisher of Practical Motorhome, provides the information in this article in good faith and makes no representation as to its completeness or accuracy. Individuals carrying out the instructions do so at their own risk and must exercise their independent judgement in determining the appropriateness of the advice to their circumstances and skill level. References to specific products are for illustration only and not intended as recommendation. To the fullest extent permitted by law, neither Future nor its employees or agents shall have any liability in connection with the use of this information. Double check any warranty is not affected before proceeding.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, why not get the latest news, reviews and features delivered direct to your door or inbox every month. Take advantage of our brilliant Practical Motorhome magazine SUBSCRIBERS’ OFFER and SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER for regular weekly updates on all things motorhome related.